|

I wish I had read this years ago, and it was a perfect complement to White Fragility by DeAngelo. I can honestly say that my understanding of issues surrounding race and racism have been dramatically altered in the last year as I've been on a quest to read more nonfiction. Although Michelle Alexander's book was published over ten years ago, it continues to be a trailblazer, clarifying history and explaining how our current social and racial structure is just another version of the Jim Crow caste system from the Reconstruction era.

Mass incarceration started as a result of a loophole in the 13th Amendment. This amendment abolished slavery except in cases where it's used as a punishment for a crime. Southern whites, angry about losing their slave labor and watching blacks become part of "their society" enacted Jim Crow laws to forcibly separate blacks from whites, preserving the best schools, jobs and neighborhoods for whites. Additionally, free blacks were arrested for committing petty crimes in alarmingly higher rates than whites. Misdemeanor offenses were elevated to felonies, and new laws were created to criminalize black life. Crimes included stealing a pig, walking beside a railroad, spitting, speaking too loudly to a woman, and selling goods after dark. These black, incarcerated men, women, and children were then leased out to private businesses as laborers. Convict leasing became a huge economic boost for the South, and it's no coincidence that arrest rates went up during cotton-picking season. A lower caste is created to keep black people from upward mobility. Michelle Alexander uses her book to point out that this lower caste system is propped up on the backs of the complex systems in place in our society. Mass incarceration is based on the label of jail and not necessarily the length of prison time. One a person is labeled a felon, they are immediately barred from ever moving up in society. Institutions in place in our country lock people of color (she focuses on black men) from being able to move from this lower caste. There are so many examples of this that I could go on forever. Some of the ones that stuck out the most to me included the traffic studies in New Jersey and Maryland. While studies showed there were actually more white people traveling on the roads, 80% of the stops were of black people, and they resulted in minimal amount of drug seizures. The Reagan-era War on Drugs has been largely ineffective in curbing drug use but highly effective at subjugating more and more black people to this undercaste system despite the fact that drug offenses are committed at roughly equal rates across races. Drunk driving rates and deaths were skyrocketing at the same time as the War on Drugs, but penalties were much higher for first-time users of crack. Statistics showed that drunk drivers were more often white males while the harsher penalties were given to black males for low-level drug offenses. Felons are not allowed on juries, can not vote, can not apply for public housing assistance, and have a nearly impossible time finding jobs. Once a person is labeled a felon, they are rarely able to better themselves. Jails were being filled up with black men during the War on Drugs, and the tough-on-crime attitude of the 80s and 90s seemed to be focused mainly on crimes committed by black people. This caste system has been perpetuated by policies created under both political parties. In the version I read, Alexander has a new Foreward that discusses this book in today's politics. She discusses Obama's record-high number of immigration detentions, Trump's tweeting of a white power supporter and calling the Charlottesville white supremacists "very fine people", Reagan's ineffective War on Drugs, and Clinton's disastrous three strikes crime bill. The Supreme Court has effectively blocked black people from legally fighting against racial bias. The ruling in the McClesky vs. Kemp case requires people to present such an impossible burden of proof with regards to racial discrimination in the justice system that it virtually makes bias and discrimination constitutionally acceptable. The layered, interlocking systems in place in our society lock poor people of color into a second class status. Alexander also points out that our nation's emphasis on colorblindness creates a racial indifference that allows these systems to stay in place, to a point where today's racial caste is no different than that of the Jim Crow era. She calls for a society where we see one another, learning and caring about our differences. When I finished reading this, I felt hopeless and sad. I can't even begin to imagine how people of color feel living with this grim reality every day. Alexander does not offer solutions in her book as she focuses mainly on research and data. I felt the need to read up on what solutions exist to combat some of the things discussed in Alexander's book. I found the Sentencing Project's Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System, and they recommend the following: *Ending the War on Drugs *Eliminating mandatory minimum sentences *Reducing the use of cash bail *Fully funding indigent defense agencies *Requiring the use of racial impact statements *Implementing training to reduce racial bias *Addressing collateral consequences I highly recommend this book if you're looking for some perspective on the complex issue of race in America. As a white person, I wish this had been required reading much earlier in my life, and I will forever sing its praises.

0 Comments

I've always been fascinated by religion especially those sects that veer off into the fundamentalist realm. There always seems to be so much secrecy and an acceptance of hypocritical thought among believers. Followers are fervent, and it's interesting to read what makes some people stay and others leave the religious communities they're raised in.

Hasids are ultra-Orthodox Jews who dabble in mysticism and practice a strict adherence to ritual laws. Deborah Feldman, assumed white, is raised by her grandparents after her mother leaves their Satmar community in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Williamsburg. Her father is mentally ill and the family doesn't seek treatment or help for him. Deborah struggles to understand why the Hasid community keeps such tightly locked secrets. She's not allowed to read secular books, and she spends her days hiding library check-outs under her mattress and stealing time to read. She questions Hasidic law and custom at every turn and feels like the adults in her life are always keeping things from her. She longs for freedom from the ritual structure of her community and finds her own ways to rebel in small doses until she eventually leaves the Satmar group for good. Married women are required to cover their hair, and many Hasids shave their heads and wear wigs. Women are required to visit the mikvah, a bath for a ritual cleansing after their periods, and Deborah talks about how uncomfortable she feels being forced to participate in the custom. Marriage is arranged by a matchmaker, and elaborate gift-giving customs are part of the engagement. Deborah is married at age 17 and completely unprepared for life with a man. Both she and her husband experience sexual dysfunction and can't initially consummate the marriage. She's horrified when her new husband's family tries to intervene and longs for privacy and a marriage that's forged out of mutual love and desire. There's a lot of controversy surrounding Deborah's version of events in her memoir. I wish she had explained Hasidic customs more in-depth as I felt lost trying to understand many of her brief recollections. Part of this may be because she didn't understand them herself when she actually wrote her story. As a reader with zero knowledge of this faith community, I was longing for more detail and background on the reasons for some of the practices. In my own personal view, religion should stand up to questioning. People who are truly curious thinkers will most likely never be satisfied with answers of "just believe" and "because this is how it is." I also find it appalling when religious groups ostracize and shun family members who choose another path. I can't get behind any system that treats people this way. I was also disgusted by how women are subjugated in Deborah's Hasidic community. Of course, this is only one perspective, and I can't assume this is reflective of all practicing Hasids, but I was alarmed by the repressive elements of her life story and can empathize with her choice to speak out. I found this to be slow and klunky at first, but strange and engrossing as I got further along. The book got me interested in learning more about these enigmatic Hasidic communities and to follow up with learning about other followers' experiences. Be prepared for this book to tear your guts out and leave them in a sloppy pile on the floor. It will make you feel like complete garbage for ever complaining about anything in your life. Catherine Gildiner is a white therapist who tells about her work with five patients suffering from traumatic life experiences. She tells their stories with tenderness and obvious fondness. Each patient overcomes the debilitating elements of his or her own emotional turmoil, finding ways to create success and exemplifying the qualities of true emotional superheroes.

Gildiner starts with a white woman named Laura, forced into parenting her younger siblings after her father left them abandoned in a remote winter cabin. Next up is Peter, a painfully shy son of Chinese immigrants, who was left alone in a room above the family's restaurant for so long that he suffered severe developmental gaps that created intimacy issues in his adult life. Although all of the stories were heart-wrenching, Danny's struck a particular nerve with me. Danny, of the First Nations, lost his wife and daughter in a car accident and was referred to Dr. Gildiner by his boss when he was unable to show emotion or feel pain after the loss. After learning more about Cree indigenous cultural norms, Dr. Gildiner helps Danny discuss his painful childhood when he was torn away from his native family and sent to a Canadian residential school designed to eliminate his identity. He was horrifically abused and spent the rest of his adult life blocking out all emotion. Alana, white and of high intelligence, was sexually abused by her father, and Madeline, also white and from a wealthy family, suffers from OCD and shares how her mother would psychologically torture her in various ways, greeting her each morning with "Good Morning, Monster." While Gidiner shares lessons from each person's story, she also discusses the mistakes she makes and how these cases helped shape her professional growth. She's quick to point out her own flaws and ways in which she could have done things differently, and this reflective quality makes me like her even more. While not for the faint of heart, this book will give you the space to consider your own emotional resiliency in comparison, and lord knows we can all use some hopeful models to look up to these days. I've been reading intense books lately, and was happy to find this murder mystery to be a bit more breezy. I finished it in two days since Lucy Foley keeps the reader in suspense up until the absolute last chapter. Right away, I felt a real Agatha Christie vibe as Foley sets the scene for a dark, moody wedding on a remote island off the coast of Ireland. I love the haunting descriptions of the harsh landscape, mucky bogs, and the stories of dead bodies stuck under the mire. The setting is crucial to the overall atmosphere of this doomed wedding. Each chapter is told from the perspective of a different person including the bride, groom, best man, wedding planner/venue owner, and some of the guests. All characters are white, except for one usher named Femi who is black. Each person begins to reveal their connection to the wedding and their motivations for being disgruntled toward one or more persons involved in the big day. This slow tease is what I enjoyed most; I had so many predictions for who would be murdered and why, and it fluctuated drastically with each new chapter. Many of the characters seem like perfectly horrid people, and Foley does a great job showcasing their flaws and even some redeeming qualities. If you like your murder mysteries to keep you guessing, you can't go wrong with this one.

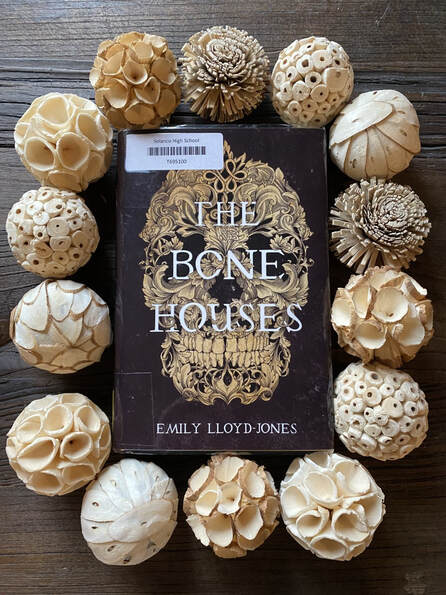

Ryn is the main character, and she's a badass gravedigger who also slays bone houses (living dead) in her spare time. This YA fantasy reads like a step back in time but it packs a modern punch. Ryn and her siblings live on their own in a small village surrounded by an iron fence built to keep the bone houses out. Much of the folklore surrounding the bone houses in Colbren is viewed as just that - old stories, but Ryn knows better. She comes upon a mysterious man named Ellis being attacked by one of the risen dead, and after she saves him (hooray for females who do the saving) she finds out he's a mapmaker who has gotten himself lost. I felt very distant from the characters when I first started reading this, and the magical elements felt too separate from Ryn's story, but I stuck with it and was not disappointed. In fact, I was riveted. Things pick up when Ryn and Ellis team up to figure out why the bone houses are suddenly attacking in mass. Some of the plot elements surprised me so much that I had to reread parts to make sure I was understanding what happened. I love when books take me by surprise.

I especially love how both Ryn and Ellis' characters were developed slowly and expertly. Ellis may have some physical weaknesses but Ryn's strengths make up for it, and they complement each other in a way that doesn't leave one overpowering the other. They become a team that isn't based on stereotypical gender roles. When Ellis is tender, Ryn is tough. They bond as orphans and the agony of not knowing exactly what happened to one of their parents. Without spoiling anything, there's also a zombie animal that plays a big part of Ryn and Ellis' journey to stop the bone houses. This decaying pet becomes their savior in many ways and was a fascinating supernatural element. Bravo to Emily Lloyd-Jones for a fantasy zombie book that is so satisfyingly unique and special. |

AuthorTravel All the Pages is inspired by my two loves - travel and reading, a combo I can't resist. Enjoy these little pairings. Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|